Kung fu & Cowboys: Facts and Fun

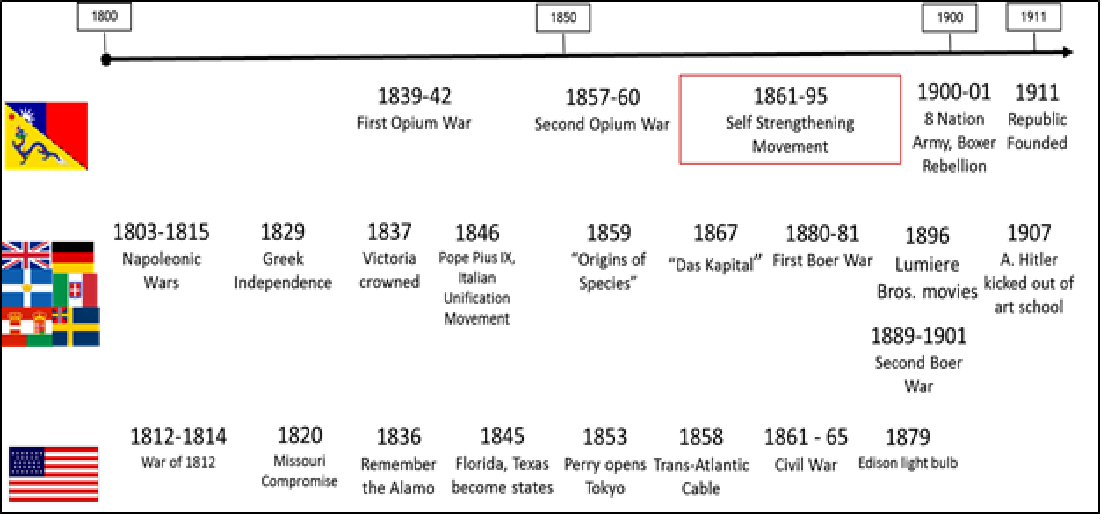

In Hung Kuen kung fu schools we often talk about the full range of martial training: spiritual, moral and physical. But what do we mean by these things? Do they exist as we seem to describe them? A set of specific “be all, end all” practices, ways and codes, rooted in mainstream Chinese history and tradition? Do these ways or codes change over time? And if they do, does that change their value? Or perhaps these traits are left overs that, while sometimes attractive, interesting and fun, do little for our martial practice?

As responsible practitioners and promoters of martial arts, we owe it to ourselves and our students to examine the historical, political and cultural contexts that led to the Hung Kuen we practice today. To understand thoroughly, we must examine each trait in turn, using history…both Chinese and European + American…to learn 1) where the non-physical traits come from, 2) their potential importance culturally and historically and 3) their effect on physical training and martial effectiveness.

Through examination of historical and cultural trends, it’ll become clear that there is little or no actual link between Hung Kuen and ancient Chinese practices, prayers or morals – not even Shaolin. Ultimately, we’ll see that the “Hung Family Fist” physical practice blossomed from a transformation of the Chinese military dating to the 1860s, and that cultural aspects of that same period “came along for the ride” as traditional military practice left the army yet remained with the populous. Later, the physical practice and cultural aspects became pop culture fodder during the 1940s – 1960s. These entertainments ultimately arrived on European and American shores “whole cloth” and were mistaken as fact…and often still are.

Where do the spiritual and ethical aspects of modern kung fu come from?

In Europe and America, martial arts are very often associated with Chinese religions. Temples are esteemed as deep wells of knowledge. Just say “Shaolin” and of course the fighting monks come to mind, or “Wudang” with its warrior priests. To a lesser degree, of course there are the claims of the Lama warriors and their patriarch Bai Mei (Pak Mei, 白眉). However, is it the spirituality that brings the martial power? Do the ethics and morals we hear in our kung fu schools stem from these religions?

The most direct answer I’ve ever heard was from Lam, Chun Fai grandmaster (林鎮輝) who laughingly asked me one day, “My family’s Catholic – you think my kung fu is any worse?!” And it stands to reason. If one were to convert to Buddhism or Taoism or Lamaism, would your kung fu abilities increase? Would you be able to sit in horse stance longer? Or punch harder? So, where does this connection between kung fu and spiritualism come from?

Certainly Shaolin has a well-deserved reputation for talented martial artists. However, that is no thanks to the Buddha, except that some of his followers were welcoming. While most military men were rejected from traditional Buddhist monastic life due to a lifetime of killing, Shaolin’s more accepting Chan (Zen, 禪) sect opened its doors. As a result, when bandits or marauding armies attacked the monastery in search of treasure, there were ex-military men who would fight back. This was a long-standing, yet questionable practice, and not well tolerated until the Tang dynasty (618 – 907). When the Shaolin fighting monks (remember: ex-soldiers!) rescued prince and future Tang emperor Li, Shimin (李世民), who in approximately 620, granted Shaolin temple…and only this temple on Mt. Song…the right to train 500 warrior monks. Naturally, this attracted more ex-military men and the temple became a research center for fighting techniques. In the centuries afterwards, other temples saw the advantage of this and also started welcoming military adepts, which led to training fighting monks. Naturally, actual and legendary exploits of these monks became exaggerated in popular fiction over time, including movies we are all familiar with!

Meanwhile, much is made of Damo and his training as the “origin story” for kung fu, however this has long been known to be false. Indeed, among the strongest objections is the difference between Damo’s Chan/Zen teaching and the practice of kung fu. (For more, see “Damo: Conspiracy of Ignorance” here).

There are more than 1,200 years from when the monks rescued Li, Shimin in the 600s, to the founding of Hung Kuen sometime in the 1800s. Many Chinese sources, for example the “Complete Practical Guide to Chinese Martial Arts” (中國武術實用), explain it like this:

“According to legend, during the reign of Yongzheng (1722-1735), a tea merchant from Fujian, Hong Xiguan (Hung Heigoon, 洪熙官) founded Hung Kuen. He learned it from Zhishan (Cheesin, 至善), while studying at the Southern Shaolin Temple, and named it “Hung Kuen” when striking out on his own.

(However), Hong Xiguan is a character in a late-Qing (i.e. 1800-1911) novel “Rhododendron” (萬年青). Also, “Hong Xi” (洪熙) is a year’s name in the imperial calendar, from the Ming dynasty (i.e. 1424). Also, the singular “Hong” (洪) word is closely associated with the Ming dynasty because the first Ming emperor called himself “Hong Wu”(洪武, note: “wu” is “martial”). In the mid-Qing dynasty (i.e. 1750s), triads calling to “overthrow the Qing and return the Ming” (反清復明) in a publication entitled “Hong Gate Questions and Answers” (洪門問答), list Hung Kuen as a primary practice, claiming it came from (southern) Shaolin. Hung Kuen spread with these triad groups through Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian, Sichuan, Shanxi, Jiangxi, Zhejian, Hunan, Hubei provinces and became a prominent style south of the Yangzi (Yangtze) (note: from 1750s-1911).”

When we examine the claims concerning southern Shaolin (see “Riddle of Southern Shaolin”) we can see that the story of Hung Xiguan (Hung Heigoon) holds no more water than Paul Bunyan in the USA. It’s a myth or folk legend. Instead, the popular Hung association became a center for political education and action, with kung fu a key component for the intended action! The link to Shaolin and Buddhist practice is simply not there.

What is there is a code of morals and ethics that would keep association members in line and make sure not to cause trouble internally, as well as ensure devotion to the cause. Take these selections from the “36 Oaths of the Hong” (洪門三十六誓) printed around 1820, some of which may ring a bell:

-

- Hong brothers will take loyalty as the highest priority; they shall not harm mothers or fathers…if they do, they will be drowned in the five lakes and their bones scattered at the bottom of the ocean.

- Hong brothers must not rely on their strength to bully the weak, they shall not contend with (the Hong) family or strive for power…if they do, they will choke on their own entrails.

- Hong brothers are bound this night to keep the association to themselves, they will not pass it to fathers or sons…if they do, and they will be bitten by snakes and swallowed by tigers.

- Hong brothers, if attacked by outsiders, have a duty to notify the association so they can all confront the attacker together…if they don’t, they will be executed.

- Hong brothers shall not boast, exaggerate or twist the truth…if they do, they will be cut apart and their bodies spread.

- Hong brothers, after taking tonight’s oath, must be loyal, honest and forthright, swearing it before all the spirits of Heaven and Earth…if they don’t, they will be burned to death and their ashes spread far and wide.

- Hong brothers shall be loyal and upright, always remembering their wives and children, they will be like the Peach Orchard Brothers (note: famous tale of Guan Yu (關於), Zhang Fei (張飛), Liu Bei (劉備), the heroes of the Three Kingdoms) and always doing what is right for their family and the country…if they don’t, they will die from a bloodletting.

- Hong brothers tonight take a most serious oath, one known to all the spirits and Buddhas; Heaven is watching; The Five Leaders will uphold them; these oaths must be heard and obeyed…if the oaths are broken, or someone starts but doesn’t finish, or isn’t day-in, day-out benevolent and righteous, he will die from 10,000 cuts, and his body spread far and wide, never to be reincarnated.

…others are clearly to keep order in the association, which is no longer needed in a modern kung fu association:

-

- Hong brothers must not gamble with other association members or allow themselves jealousy when seeing silver won by their brothers…if they do, they will die from 10,000 cuts.

- Hong brothers shall not contend over women; elder brothers have their portion, young brothers have theirs…if they do, they will die spitting up blood.

- Hong brothers shall not take planted fields for their own, or plunder other’s harvest…if they do, they will die from 10,000 cuts and their body spread to the five directions.

As time went by, the Hong association continued to refine their oaths, rules and strictures. I’m sure they become more recognizable to those attending kung fu school, or simply deep fans of kung fu movies. For example, the “10 Proscriptions” (from approximately the 1870s)…

-

- Those who show no filial piety (loyalty to family) will receive 108 hits with a staff.

- Those who reveal our secrets will receive 108 hits with a staff.

- Those who make trouble will receive 108 hits with a staff.

- Those who play their brothers for fools will receive 108 hits with a staff.

- Those who drink and cause fights will receive 72 hits with a staff.

- Those who break the bonds of our brotherhood will receive 72 hits with a staff.

- Those who cheat or gamble will receive 72 hits with a staff.

It is from rules like these, rules that organized a political and martial society for several hundred years, that our modern European and American perception on the “ethics, morals” of kung fu come from – not Buddhism, Taoism, or any other religion.

But how did they get from secret Chinese martial societies in 1800 to 2016 kung fu schools? Read on! (Spoiler alert: it’s pop culture.)

Where do the physical aspects of modern kung fu come from?

To understand modern development of martial arts, we must first dispel the perception that kung fu is “ancient.” So, which of the following would you consider “ancient”?

- Light bulb

- Trans-Atlantic cable

- “Das Kapital”

- “Origins of the Species”

- Movies

- US Civil War

- Victorian era

- Boer Wars

- Italian unification

- Cowboys

- Hitler

- Napoleon

None? Right! Of course they’re not ancient. Knowledge about these events are recorded and available. While writing about Napoleon is likely more readily available, and of higher quality in French…still, we can investigate. Equally, German might help with “Das Kapital” and English with “Origins of the Species.” The same is true about kung fu – with Chinese language, material beyond pop culture is available.

So, why do we often treat kung fu history, tradition and culture…as if it is inaccessible and far removed? Could it all be a marketing ploy? Or perhaps popular imaginings run amok?

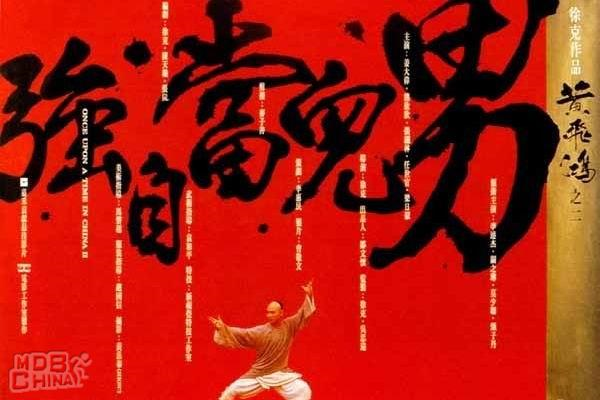

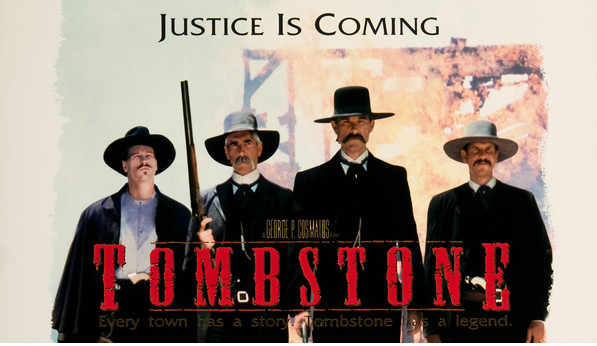

One likely reason is we have simply accepted the historicity of folk lore. Another reason might be the enjoyable popular media about Shaolin or Wudang, and even martial heroes like Wong Fei Hung (黃飛鴻). However, these stories have the same problems that American cowboys suffer. For example, watch any movie about Wyatt Earp’s gunfight at the O.K. Corral and compare them to the personal accounts, and court documents of the actual event.

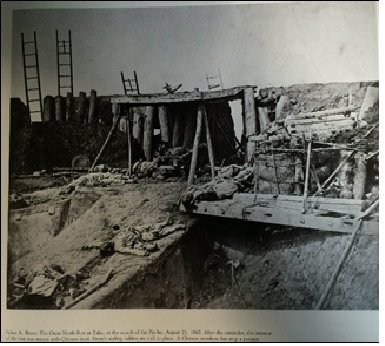

Therefore, as responsible practitioners and promoters of martial arts, we owe it to ourselves and our students to examine the historical, political and cultural contexts that led to the Hung Kuen we practice today. Indeed, we can easily see that our “age old” martial traditions trace their roots back to the mid-1800s. To clarify our understanding of martial arts with history, we should understand the crucial push and pull of modernization in China at that time, perhaps best exampled by the “Self-Strengthening Movement.”

The effects of the “Self Strengthening Movement” are summed up in the “Comprehensive History of Chinese Military Studies” (中國軍事通史) [with my emphasis added]:

“The changes in military education in the later Qing dynasty era began in the mid-19th century, around 1860, coinciding with the western incursions. Before this time, in accordance with earlier traditions, leadership was chosen by two main methods: military achievements (軍功) and martial (arts) skills (武舉). Those earlier methods had tests in archery, swordsmanship, formations and so on, as well as selection from the populous of highly skilled martial artists to become squad and battalion leaders. These selection methods had been passed down from the long era of “cold steel” armies and warfare, which they had proven suitable for. However, with the changes of the times, and hand-in-hand with scientific advancements, the Chinese military firmly entered the era of firearms. In this way, the traditional strategies and tactics, as well as the organization of squads and battalions, had decreasing objective value and force. As a result, studying western technologies and techniques, alongside instituting modern military education, training and insights into promoting a new kind of military talent inevitably led to historic changes.” (Vol. 17, Sec. 2, pg. 1102)

This short paragraph highlights a sea change in culture that forcefully happened in approximately 50 years. As mentioned in another article, Li Hong Zhang (李鴻章) is an exemplary figure of this transformation because initially he was against the changes, continuing to believe Chinese culture was superior “in and of itself” and wishing to maintain the “old ways.” However losing bitter wars convinced him to change and he took charge of building modern arsenals and armies.

As this relates to martial arts, we should note how the selection of military leadership changed from “show me your kung fu” to “attend a military academy” and ask: what happened to those whose kung fu was excellent, but no longer had a professional career path into the military? Our own Hung Kuen history provides excellent clues.

Wong Kei Ying (黃麒英, 1810 – 1886) and Wong Fei Hung (黃飛鴻, 1847 (or 1856) to 1924/25) can easily be imagined struggling with the shift described. After all, in the early 1800s, martial artists could have still reasonably expected to earn leadership positions in the army, as they had done for a long time. Yet, by the 1860s (as Fei Hung became an adult), signs that the military career option was ending must have been increasingly clear. Importantly, according to the “Comprehensive History of Chinese Military Studies” the southern region was one of the slowest to modernize. This created windows of opportunity for martial artists in the south to both maintain links to military hierarchies and men, as well as also explore alternative careers. (By contrast, in the center and north, armies more rapidly transformed in order to protect those areas not yet lost to invasion and rebellion.) Tellingly, we see Kei Ying opening the famous clinic in 1886 and Fei Hung openly teaching kung fu and acting as security (保鏢) from then through the 1920s (e.g. joining the Ching Wu Men Society (廣州精武體育會) in 1919). [Wikipedia (https://zh.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E9%BB%83%E9%A3%9B%E9%B4%BB)]

Obviously these simple examples reflect the cultural transformations of the time. People formerly training for one career route find themselves opening a new one. However, as they did so, can we truly believe that they encapsulated ancient martial values into teaching of the time? Or is it reasonable to expect that they tailored the promotion of the clinic and kung fu teaching to attract students and attention? In short, did they truly reflect a single, ultimate “ancient martial tradition” or was the particular recipe formulated and baked, based on the needs and fashions of the time?

Wyatt Earp (1848 – 1929, a contemporary of Fei Hung!) could likely answer the same question and reflect on similar issues with “cowboy values” of the “old west” and how they paradoxically never existed and yet still exert influence over modern minds. The ideals that came to be embodied in stories of the O.K. Corral gunfight were not really on the minds of cowboys at the time. They were worried about making a living in the rough and tumble silver mining of Arizona! Similarly, it is likely that Fei Hung was less interested in preserving martial values as he was in marketing his school and clinic. In this sense, reflecting a bastion of solid tradition as tumult was all around was likely a winning play. Indeed, the popularity and notoriety gained seems to be the proof in that pudding. Likewise, Earp was recruited – and mourned – by famous Hollywood stars to promote “tradition.” Of course, having excellent skills…whether in kung fu or quick draw…didn’t hurt. However, the tradition promoted in both Fei Hung and Wyatt’s cases is not reality – it is merely popular imaginings.